Mychal Denzel Smith’s memoir reckons with racial injustice, and tells the story of his political education.

As Imani Perry recently observed in an essay for Public Books, the past few years have also seen a resurgence of interest in black memoir. Black autobiography, from the slave narrative to the modern memoir assumes that an individual’s experience can speak for a racial experience broadly shared. This assumption has endured even as black life in America has become increasingly complex and often divergent. The risk with this, Perry writes, is that black memoirs today, “are often read as saying much more than they actually can about the broader experiences and thoughts of Black people.” The burden heaped upon books like Coates’s Between the World and Me, Margo Jefferson’s Negroland or Clifford Thompson’s Twin of Blackness—is always greater than they can be expected to bear.

If we are truly to “acknowledge the widely ranging experiences of Black people across lines of class, gender, identity, region, education, sexuality, and ethnicity,” then no single voice, Perry cautions, “can stand as a singular representation of black life, regardless of how compelling it might be.” Instead, she asks us to imagine black memoirs as hollers in a ring shout, each one “understood as one cry in the ring, a small piece of a mosaic, vast and ever changing.”

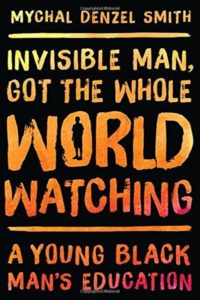

Mychal Denzel Smith’s new memoir, Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching, is a voice entering the ring with fire. With raw urgency, intelligence and blistering candor, it tells the story of a young man’s political education. His story is refracted through the turbulent first decades of the new millennium, a period shaped by the global War on Terror abroad, the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina at home, and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has challenged the nation to end its long history of unchecked and unpunished police brutality in minority communities.

As such, it is an opportunity to reflect on what has changed in our politics over the course of the Bush and Obama years, and in particular on the reemergence of an activist consciousness in black politics (and youth politics more broadly.) If Smith were merely telling that story, his book would make an interesting contribution to contemporary political commentary. But it is his pointed self-examination that makes it rarer and altogether more valuable, a book that gives us stories about how we learn to change, and not just arguments about why we should.

Smith has been a contributing writer for The Nation since 2012. The story of how he came to write his first piece, “Justice for Trayvon Martin,” is at the center of his narrative. “I was twenty-five years old when George Zimmerman killed Trayvon Martin,” he writes. “I hadn’t prepared for life at twenty-five, having believed at different points of my life that I wouldn’t make it that far.”

Trayvon’s killing prompts him to seek answers through investigative journalism. But more importantly he seeks the meaning of his own survival in contrast to Trayvon Martin’s death, and the world in which both fates were possible:

I wanted for him, for all the Trayvons in waiting, a world where they didn’t have to grow up broken or not grow up at all. I wanted to figure out how to create that world. I looked at my own life and asked how I made it to twenty-five…I asked myself: How did you learn to be a black man?

What follows is Smith’s attempt to answer that question, by retracing his path into adulthood, the birth of his political consciousness, and his vocation as a writer. Many pivotal moments in his life coincide with national events and crises; others relate to his personal and family life. No doubt, tragedies that dominate the news cycle do come to shape who we are and our views about the world; but the notion that they are primarily what shapes us risks suturing the individuality of Black lives to grand narratives about Black Life in America in ways that flatten them into the fodder of CNN special reports, precisely the opposite of what Smith sets out to do here.

This is why the best pages of Smith’s memoir are not those in which he reads events like the Jena Six trial, Lebron James’s decision to go to Miami, or dissects figures like Dave Chappelle or Kanye West, an artist he astutely recognizes as an avatar for a newly assertive but anxiety-ridden black middle class. The most compelling moments come when he uses his personal experience to shine a light back on his politics—where his unflinching honesty allows us to share in a sense of greater awareness dawning on him, along with compassion and sometimes doubt.

Smith has an important realization—the first of many—at Hampton University on the campus newspaper. There he becomes something of a thorn in the side of the administration for his polemical stances, but more importantly, he comes to recognize not just the limitations of his institution, but of his own unexamined endorsement of a charismatic, masculine black politics. “To my newly forming black radical mind,” Smith writes, “women—more specifically, black women—had a way of existing without being present.” He arrives at this wisdom not abstractly, but through acknowledging his own debts to his co-editor at the paper, Leslie. “I reaped the benefits of her emotional and intellectual labor without ever asking how I could support her,” he acknowledges. This attitude, Smith observes, is no accident, but the pernicious legacy of a tradition within black protest that has repeatedly cast it as primarily a “fight to restore dignity to black manhood.” He offers himself as an example of how one can outgrow and think through certain fossilized attitudes and eventually shed them.

We get an excellent example of this in his exploration of the roots of his casual homophobia. I suspect many readers will be able to relate to Smith’s description of his earliest understanding of the term “gay,” as it got thrown around in the schoolyard:

Being assigned homework on the weekend was gay. The cafeteria not serving pizza was gay. And any person suspected of being gay, we called a faggot. And then we laughed. And then the person being called a faggot got angry. And you never really recovered from the charge, unless you could prove someone else was the faggot. And all of this made sense to us.

Smith outgrows the schoolyard slurs, but finds this is only the beginning of a longer struggle over sexuality and ethics. He tests his own attitudes against those of his father, who “wouldn’t curse or drink liquor in front of me” he writes, and yet in spite of that rectitude, “calling people faggots was alright with him.” When his roommate at Hampton starts dating another man, he revels in a shallow vindication of his adopted progressive politics that he soon realizes is an impoverished form of human acceptance: “I lived with two gay men, how could I be homophobic? […] I’d watched Brokeback Mountain and didn’t turn away once, how could I be homophobic?” Being gay was a matter for others and not for him to deal with: “I wasn’t afraid of gay people, or of witnessing expressions of same-sex attraction. I was, however, afraid of someone believing I was gay,” he admits.

He listens to Frank Ocean’s Channel ORANGE and struggles to sing along: “Frank Ocean pining after a man still felt ‘unnatural.’ The fear was no longer there, but my tongue hadn’t caught up to my politics.” Perhaps most crucially, he disavows the homophobic traces in his own black revolutionary politics, those currents in some black nationalist discourse that have attacked black gay men as “weak, deceptive, traitors,” who “undermine our collective manhood.” In its place he urges us to begin, “unpacking our identities that have been rooted in archaic notions of masculinity and sexuality, and embracing the parts of ourselves we’ve been taught to reject.” Borrowing the words of writer and activist, Darnell L. Moore, he reminds us that, “Black liberation is love. And love is the act of removing any barrier that keeps us apart.”

Smith pushes us to expand our empathy to others, but he also bravely advocates improving the care we afford ourselves. In a beautiful set of vignettes he describes grappling with a sense of survivor’s guilt after the loss of his cousin Demetri to gun violence. He connects that pain to a series of panic attacks, and ultimately an acknowledgment that he is suffering from depression. “No one in my life when I was twenty-one years old would have said they had depression,” Smith writes. “The only people I ‘knew’ who had gone to a psychiatrist and would talk about it openly were white people in Woody Allen movies.” It’s true, mental health remains a major taboo in black life. For a population exposed disproportionately to high levels of violence and trauma, the stigma attached to mental health and the lack of serious initiatives for addressing an expansion of care are unacceptable.

This too, is part of Smith’s political education, and it would be a great achievement if his example can inspire us to do better when it comes to normalizing discussions of mental health and black life.

Hip-hop heads will recognize the title of Smith’s book Invisible Man…. as a doubled allusion. The first is a reference to Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel, Invisible Man, in which Ellison’s ‘underground man’ recounts his (sometimes surreal) experiences navigating a formal education in the South, a political education in the North, and the threat of riots in a time of boiling racial tensions. The second comes from Mos Def’s track “Hip Hop” on his classic 1999 album, Black on Both Sides:

We went from picking cotton

To chain gang line chopping

To Be-Bopping, to Hip-Hopping

Blues people got the blue chip stock option

Invisible man, got the whole world watching…

In these lines, the rapper takes note of the historical trajectory of black life in America and the paradoxes of that legacy in his own fame, updating, as it were, Ellison’s metaphor.

Smith is also interested in updating the trope of visibility, in his case to tie it to the spectacular politics of online activism. In our day, “the Internet,” as he puts it, “became the new grassroots.” “Twitter made it easier to make the invisible men visible,” Smith writes, arguing not just for the importance of social media is an organizing tool, which it undoubtedly is, but for its ability to increase empathy, to force others to care about people who previously did not matter to them. Playing explicitly on Ellison’s famous prologue, he argues that, “through social media, the substance of our existence was made real for the rest of the world.”

No one, I think, would disagree with Smith that the Internet has opened important avenues for shedding light on racial injustice. But Ellison was getting at the very important fact that invisibility is not a function of what people see, but how they interpret what they see; Ellison’s narrator says that his invisibility to others is “a matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality.” His invisible man likens his condition to that of certain “circus sideshows,” and adds that, “it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass.” Is social media capable of making “the substance of our existence” real to the world? Or is it more like Ellison’s warped looking glass, capable of reproducing as much harm and unreality and caricature as any other medium? Isn’t the problem not what we see but what kind of readers we are, what kinds of stories we’ve been told? This is what determines whether or not we really see each other.

If we are ever going “to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country,” James Baldwin famously wrote, “we must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others,” that is, of those Americans who continue to insist that they are blameless, that they can evade the crimes of the past and the injustice of the present. Achieving our country today can seem, in some ways, just as remote and ideal a possibility as it was in 1963 when Baldwin wrote those words. On the other hand, unlike then, there really has been a sea change when it comes to the number and plurality of black voices with authority in the public sphere. There has never been a First Lady, like Michelle Obama, telling America the truth of her past so directly, as she did at this year’s Democratic Convention; a truth so fiercely and eloquently stated that the gatekeepers of white America simply could not believe it.

We are living in a time of vertiginous contradictions. The Obamas on the lawn of the Whitehouse; Philando Castile bleeding out in the front seat of his car. Across this abyss of senselessness and injustice, the creation of a new consciousness is daunting but also more tantalizingly plausible.