Forthcoming from University of Chicago Press in Spring 2024

Forthcoming from University of Chicago Press in Spring 2024

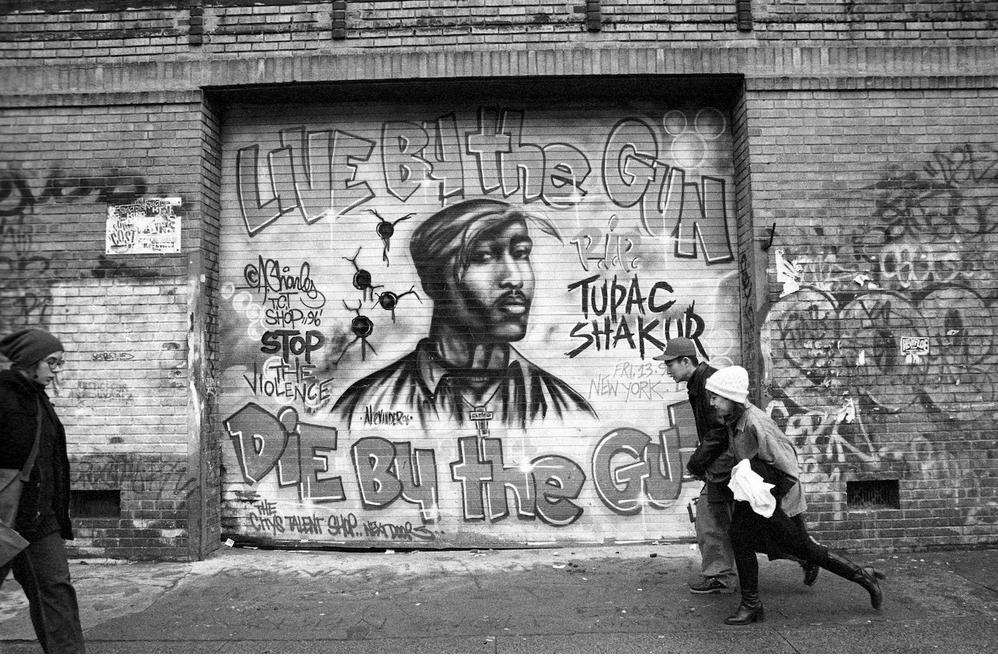

‘Tupac Shakur’ captures an icon’s spark and decades of Black history

Staci Robinson’s authorized biography covers the rapper’s early life and private life as well as the years of global fame

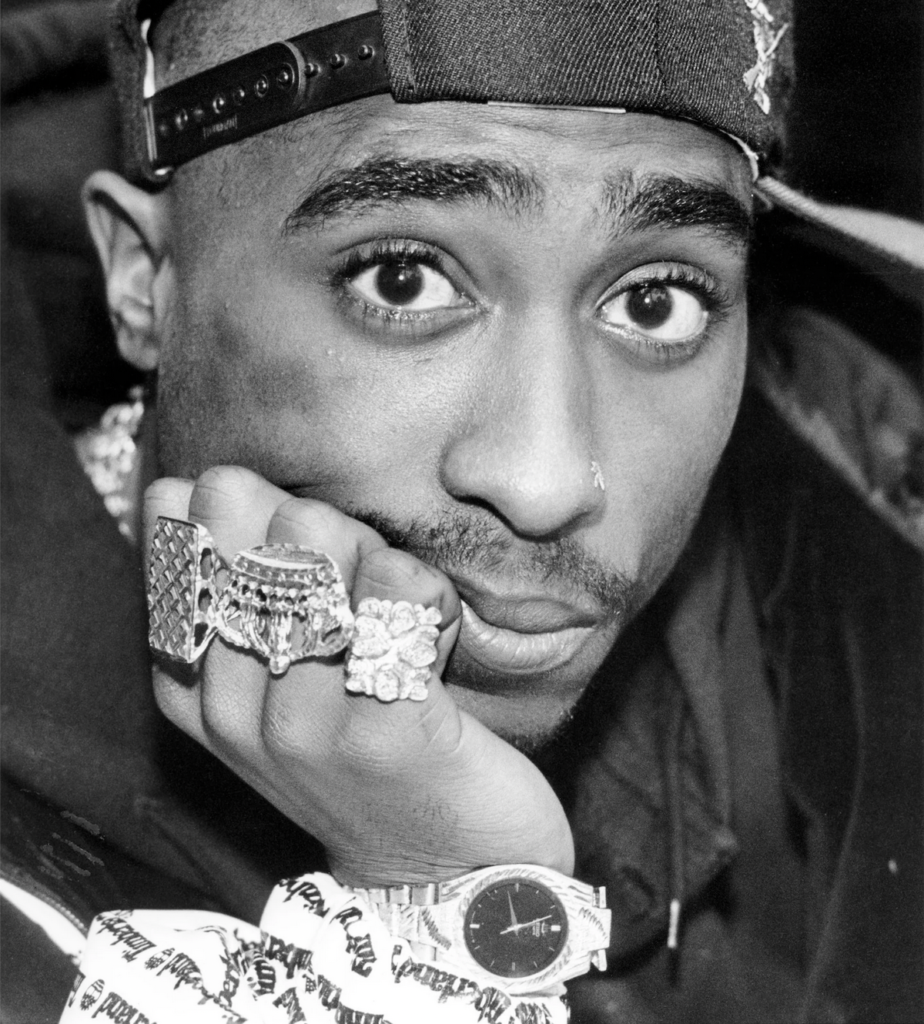

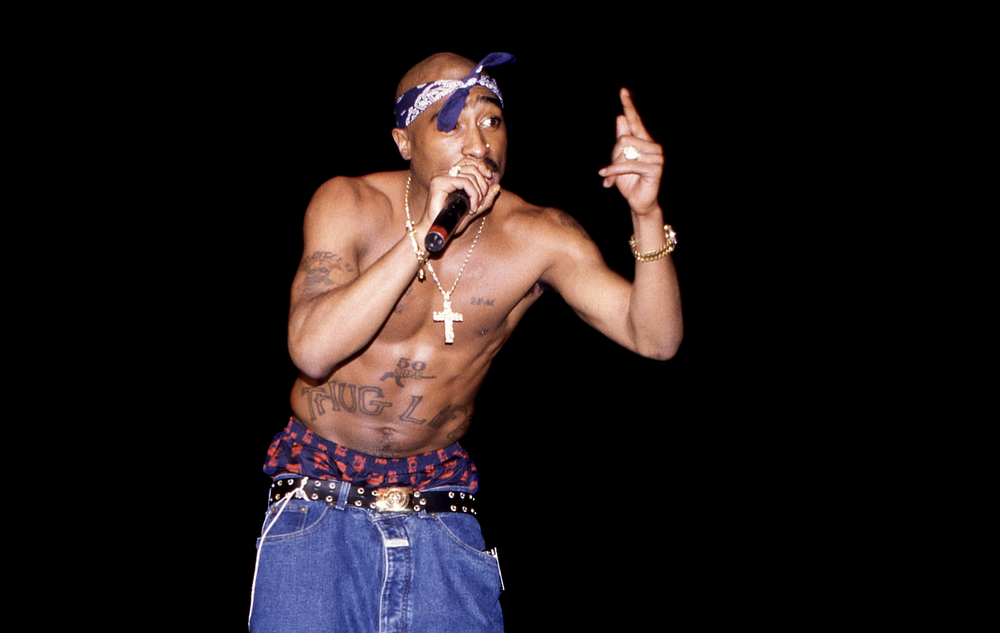

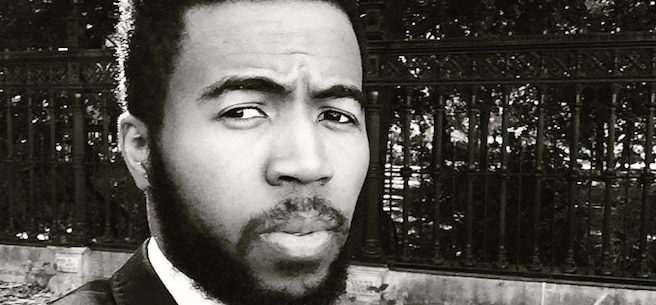

Tupac Shakur in 1992. A new authorized biography traces the rapper’s early life and his rise to global fame. (Gary Reyes/Oakland Tribune Staff Archives/Bay Area News/Getty Images)

In the winter of 1971, Afeni Shakur, a 24-year-old Black revolutionary on trial in a case for which she had — against all advice — insisted on conducting her own defense, secured pen and paper and carefully wrote out a letter to “the unborn baby within my womb.” From her cell in downtown Manhattan, she wrote:

I’ve learned a lot in two years about being a woman and it’s for this reason that I want to talk to you. … I’ve discovered what I should have known a long time ago — that change has to begin within ourselves — whether there is a revolution today or tomorrow — we still must face the problem of purging ourselves of the larceny that we have all inherited. I hope we do not pass it on to you because you are our only hope. You must weigh our actions and decide for yourselves what was good and what was bad. It is obvious that somewhere we failed but I know it will not — it cannot end here.

It would not end there. Afeni gave a rousing speech before the court that moved the judge to release her from custody pending the verdict, which arrived 10 days later. All the defendants in the “Panther 21” case, as it was popularly known, were eventually cleared of the terrorism charges against them, as the prosecution’s largely circumstantial evidence failed to convince the jury.

The baby, a boy, was born on June 16, 1971. Afeni gave him two names. For the government to put on his birth certificate, she chose Lesane Parish Crooks, a combination of the names of women who were important in her life, including her sister’s family and the lesbian women she had befriended in jail. She had adopted for herself the nom de guerre Afeni, a Yoruba name meaning “Dear One” and “Lover of People.” She gave her son a revolutionary name as well, the name of the last leader of the Incan resistance against the Spanish conquistadors, a name she intended to evoke the spirit of all Indigenous peoples of the world in their struggle against all forms of colonial oppression: Tupac Amaru Shakur.

The iconic rap artist the world knows as Tupac Shakur (and by his stage name 2Pac, and often, affectionately, just Pac) was born, as Afeni prophesied, into the chaos of a collapsing revolutionary movement that had sought to reshape the cultural consciousness and the communitarian political will of Black America. The story of his brief and turbulent life is also an epilogue to that failed revolution: a symbol of the terrible costs that have accumulated, and continue to climb, as the legitimate aspirations that aroused that political fervor continue to be deferred, denied or simply abandoned.

Tupac Shakur performing at the Regal Theater in Chicago in 1994. (Raymond Boyd/Getty Images)

By the time of his death in 1996, at 25, Tupac had made himself into one of the most admired and reviled, most beloved and hated, most envied and feared Black men in America. His body, his face and, above all, his voice broadcast the figure of the gangster rapper, a composite of underclass resistance and hedonistic rage. A global celebrity of the MTV era, he embodied stunning contradictions: sincere revolutionary anger and care for the oppressed, entrepreneurial amorality and aggression, and a flair for capturing the pop-cultural zeitgeist. He was the heir to Che Guevara, Frank Lucas and Michael Jackson all at once.

Tupac has been the subject of a biopic and numerous documentaries and books, including a collective biography released earlier this year, Santi Elijah Holley’s “An Amerikan Family: The Shakurs and the Nation They Created.” The vines of myth have grown around him, producing a sprawling martyrology and a raft of conspiracy theories about the shooting in Las Vegas on Sept. 7, 1996, that led to his death a week later. This September, 27 years after the fact, the Las Vegas Police Department announced that it had arrested Duane Keith Davis, who has long been suspected of involvement in the shooting along with his nephew Orlando Anderson (killed in a probably unrelated shootout in 1998). Given these decades now of rumor, gossip and lore, one might wonder if there is anything left to say about Tupac, or any way to get a reliable picture of a subject whose turbulent legacy is indelibly woven into the tremendous impact of his art.

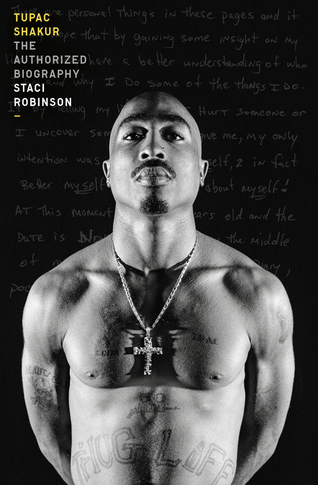

(Crown )

It turns out there is. Staci Robinson’s “Tupac Shakur: The Authorized Biography” gets its authorization from none other than Tupac’s mother, who asked Robinson to chronicle her son’s life. Robinson is a screenwriter and novelist. She was also a high school friend of Tupac’s who has been on intimate terms with what she calls “Tupacland” since the early 1990s. A first draft of this biography was completed in 1999, when interviews and memories were still fresh, even raw. The project was sidelined, however, then revived in 2017, when Robinson became involved in the curation of a museum exhibit about Tupac’s life. Robinson is humble and even self-deprecating in her preface, explaining that she often felt inadequate as a writer, given the monumental task at hand. But she persisted because of a sense of duty and the faith that Afeni Shakur placed in her.

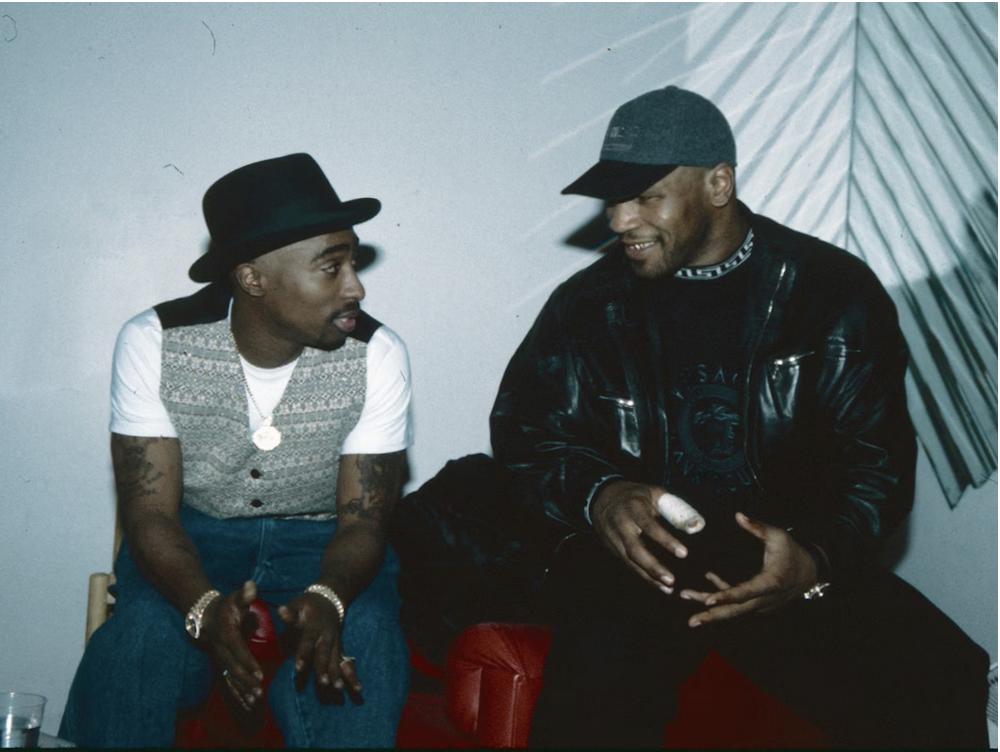

The greatest risk of such a book is always hagiography; proximity to a subject and their family and friends can easily become detrimental to honest assessment. While reading, I braced myself whenever the narrative approached one of the highly charged, well-publicized episodes in Tupac’s life. There’s the shooting of Qa’id Walker-Teal, a 6-year-old boy who was killed by a stray bullet in 1992 when a brawl broke out between Tupac’s entourage and gang members in Marin City, Calif., who felt the rapper had disrespected them. There’s the shooting at Quad Studios in New York, where, during a robbery in 1994, Tupac was shot five times, an incident he forever believed was a setup that involved Christopher Wallace, a.k.a. the Notorious B.I.G.; the shooting led to a poisonous rivalry that engulfed the entire rap scene and that many have blamed for both rappers’ murders. There are the 1993 sexual assault allegations by 19-year-old Ayanna Jackson, regarding events in a hotel room with Tupac and several of his associates; Tupac was acquitted of the most serious charges but was sentenced to 4½ years in prison for first-degree sexual abuse, characterized in the verdict as “forcibly touching the buttocks,” for which he ultimately served 11 months. Then, of course, there’s the fateful night in Las Vegas when, just after the Bruce Seldon-Mike Tyson fight at the MGM Grand (Tupac had composed Tyson’s entrance music), Tupac and his entourage beat up Orlando Anderson, on the grounds that Anderson had robbed someone in Tupac’s entourage of their specially crafted Death Row Records chain. (The irony of the contentious object is unavoidable.)

Staci Robinson, author of “Tupac Shakur: The Authorized Biography.” (Shauna Heidenreich)

Robinson gives each of these events its fair share of attention and treats them with a relatively, though not entirely, unbiased eye. She never veers into outright apology or mitigates or conceals troubling details. Unless one is an insider to these events, of course, it can be hard to tell how much a biographer is strategically withholding or emphasizing.

The one person I wish we learned more about in the book is Keisha Morris, who was studying criminal justice when Tupac met her in 1994. They were married in 1995 at the Clinton Correctional Facility, in Dannemora, N.Y., when Tupac was incarcerated there. While their relationship was brief (they divorced before his death), some of the book’s most tender moments center on the downtime Robinson describes the couple sharing in Keisha’s Harlem apartment: Tupac scribbling lyrics on notepads while the cocker spaniel that he bought to keep her company nips at his toes; cooking for each other; Tupac insisting on taking Keisha to see his favorite show on Broadway, “Les Misérables.”

Robinson perfectly captures these everyday moments. Strangely, on balance, you almost feel like you’re reading about the life of an ordinary person. This impression is reinforced by the inclusion of facsimile pages from Tupac’s school notebooks, which range from his favorite Robert Frost poem, “Nothing Gold Can Stay” (which he would occasionally recite from memory throughout his life), to the delightfully adolescent poem “4 Jada,” about his crush on Jada Pinkett (now Jada Pinkett Smith), his classmate at the Baltimore School for the Arts. Robinson weights the book toward the rapper’s early years, a welcome decision that lets us see the complex layers of his private life, which was eventually eclipsed by his celebrity, the sensationalism of his swaggering persona and the shock waves of his violent death.

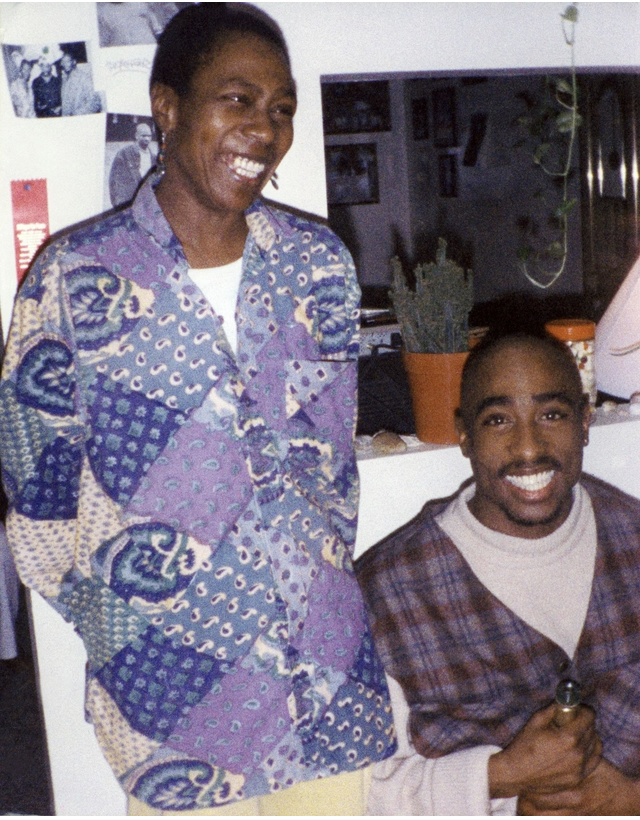

Afeni Shakur at the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, 1970. (David Fenton/Getty Images)

Tupac’s youth was shaped by his mother’s efforts to put her life back together and provide security, stability and education for her family. Afeni had joined the Black Panther Party in 1968 and quickly married Lumumba Shakur, the minister of defense for the Harlem chapter of the Panthers. The relationship, strained by Afeni’s trial, ultimately ended in divorce. She became close with Billy Garland, a Panther from Jersey City who was supporting the members on trial, and Kenneth “Legs” Saunders, “a lieutenant of the famed drug lord Nicky Barnes.” Afeni had relationships with both men, and when Tupac was born it was not immediately clear that Garland was his biological father. After gaining her freedom, Afeni continued her political activism and worked on drug prevention programs in New York, where she crossed paths with Mutulu Shakur, another young revolutionary, who had also taken that surname to indicate his dedication to the Black freedom struggle. Mutulu was a foundational member of the Republic of New Afrika, which had drafted plans to create a separatist state for Black people by forcing the U.S. government to “free the land” between Louisiana and South Carolina. When Tupac was 4, Afeni gave birth to a daughter with Mutulu, Sekyiwa Shakur. The family moved through several homes in Harlem and the Bronx, and spent significant time living with Afeni’s sister Jean and her partner Thomas “T.C.” Cox, who worked for the New York Transit Authority.

All of this meant Tupac grew up with conflicting models of masculinity and fatherhood. Mutulu taught him about politics, imparting lessons about colonialism, imperialism and America’s “capitalistic power structure.” He was also a “healer and an acupuncturist,” who made all the children in the household do stretches in the morning, instilling in Tupac a lifelong devotion to physical fitness. T.C., a hard-working man with a steady job, offered an example of stability and an ethic of generosity and kinship beyond blood relation. Legs was a hustler and streetwise man who claimed Tupac as his son and bought him as an early gift a boombox with cassette players and extra-large woofers. Legs, too, was keen on health and nutrition, and we learn that the Shakur children would listen “with rapt attention as he offered detailed explanations of the benefits of cod liver oil and the positive effects of bee pollen.” He also would sometimes disappear without warning, and he died in 1985 of a heart attack. He fell prey to a scourge that would deeply mark Tupac’s life: the massive influx into Black neighborhoods of freebase crack cocaine, a side effect of President Ronald Reagan’s covert foreign policy moves in Central America and the Caribbean.

In the interstices of this tangle of poverty, instability and radical Afrocentric politics, one glimpses little moments that portend something no one could have foreseen. We see preteen Tupac in deep focus on his karate moves at the Black Cipher Academy, a dojo in Harlem run by a former Panther with “posters of Malcolm X and Che Guevara” lining the walls, where “Tupac always took out the garbage and wiped down the mirrors” in “exchange for the class fee, which Afeni couldn’t afford.” We see Mutulu teaching an 11-year-old Tupac “about the intricacies of haiku.” Tupac was “fascinated by its 5-7-5 meter and started to craft his own poems,” Robinson writes, dedicating them to the heroes in his life, the incarcerated Black revolutionaries he prayed would one day be free. We see him playing Bob Marley’s “Exodus” over and over on his special boombox. And we see this passion for music and poetry complemented by a magnetic stage presence in 1984, when Tupac, 13, performed the role of Travis Willard Younger in Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” at the Apollo Theater in Harlem.

Afeni Shakur and Tupac Shakur in a photo seen in the director Lauren Lazin’s 2003 documentary “Tupac: Resurrection.” (MTV/Amaru/Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock)

Just as Tupac was beginning to flourish, his mother was slipping into an addiction to freebase cocaine, which Legs had introduced into her life. In the fall of 1984, Afeni and the children moved to the Baltimore neighborhood of Pen Lucy, one of the city’s “notorious drug zones.” Unlike megastar rappers such as Kanye West and Drake, who strike the street-tough pose but grew up solidly middle class, Tupac knew real poverty and deprivation in his youth. His makeshift bedroom had been converted from a patio. On the thin plywood walls with no insulation, he hung posters of his idols, including LL Cool J, Bruce Lee, Sheila E. and New Edition. Rats regularly raided the kitchen, and the family survived on food stamps. Tupac had secondhand pants that didn’t fit: “He quickly hemmed them with staples before he left for school.” Despite these hardships, life in Baltimore was a period of discovery for him. When the electricity would get cut off because of an unpaid bill, he later recalled, “I used to sit outside by the streetlights and read ‘The Autobiography of Malcolm X.’”

Tupac adopted the name Casanova Kid, then quickly dropped that in favor of MC New York after he teamed up with a sidekick named Mouse, an expert beatboxer. Together they wrote rhymes on the city bus and entered rap and poetry competitions. The first prize Tupac ever won was for a rap called “Us Killing Us Equals Genocide.” His second significant song was “Library Rap,” a lyric in praise of reading and knowledge. At the Baltimore School for the Arts, he flourished as a rowdy art and theater kid who was finally among his own. He made friends with Mary Baldridge, a dancer and the daughter of the director of the Communist Party of Maryland; Tupac had his first brush with formal politics during the 1987 Baltimore mayoral race, when he and Mary campaigned for Kurt Schmoke, who would become the city’s first Black mayor. Tupac’s tastes continued to broaden. He became enthralled by Don McLean’s song “Vincent” from the album “American Pie,” which developed into an enduring interest in the life and paintings of Vincent van Gogh.

But poverty and addiction would force another move, this time to Marin City, a Black ghetto in the otherwise wealthy Marin County headlands north of San Francisco. The streets of Marin were awash in drugs, and the artsy Tupac, who walked around with a rhyme book and a CD of the “Les Misérables” soundtrack in his back pocket, stuck out at Tamalpais High School. “He’d wear the same thing every day, jeans and a jean jacket, and he had a Gumby haircut back then,” a friend from Tamalpais later recalled.

Tupac drifted away from school; he dropped out in 1989 but found community in a multicultural youth support group led by Leila Steinberg, a Bay Area activist. Steinberg immediately sensed his exceptional qualities: “Tupac showed off his wide-ranging interests, reciting a passage from ‘Moby-Dick’ or adapting lines of ‘Macbeth’ before quickly switching genres to offer his opinion of Iceberg Slim’s memoir, ‘Pimp.’” Robinson gives us a portrait of the artist as a young man, a restless spirit convinced of the greatness of his destiny, if unsure of his destination. At the crossroads, we overhear the contradictions of Tupac the aspiring star but also those of his time and place, California at the start of the 1990s. “All I want in my life is to have a record out and be in a movie. That’s all I want. And if I can’t do that, I’m going to be president of the New Afrikan Panthers,” Tupac told an interviewer.

Tupac Shakur with Mike Tyson in Las Vegas, circa 1996. (Nitro/Getty Images)

The rest of the life unfolds as if the Fates, or perhaps the Furies, are listening. On Aug. 15, 1991, Tupac became the first rap artist ever signed to Interscope Records. His recording career would last barely five years — long enough for him to achieve global stardom. He released four studio albums, starred or had a leading role in four films, and caroused with celebrities like Madonna, Mickey Rourke and Janet Jackson. On April 1, 1995, he became the first musician to hit No. 1 on Billboard while incarcerated, when his third album, “Me Against the World,” debuted at the top spot. Hundreds of thousands, then millions of dollars rolled in. Houses with pools, flashy cars, drives from the movie studio lot to the hood: The Tupac tornado was unleashed, and everywhere he touched down, flashes of lightning punctuated the storm.

In an age of spectacle, Tupac understood the power of projection, of fantasy, the deep craving in the American psyche for the outlaw who comes riding out of the West with a nihilistic taste for freedom. To be a young Black man in the age of Tupac was to be very afraid and very excited about a cliff top of power, one tantalizingly within reach, that you surmounted only by courting the abyss, the near-certainty of violent annihilation. Yet there he was: wrathful and proud like a wronged Monte Cristo, making it clear with a single look that A Nation of Millions Could Not Hold Him Back. Our poète maudit, aloof and gorgeous, sly and playful, rude and lewd, a gothic avenger, caroming through courtrooms, being everything we were told to be — and not to be. A hypermasculine sex symbol who had an image of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti, “a symbol of feminine power and beauty,” inscribed on his chest, and who, on “Keep Ya Head Up,” affirmed in his lyrics a woman’s right to choose: “And since a man can’t make one/ He has no right to tell a woman when and where to create one.” Here, too, was the sensitive poet whose midsection sported his most notorious tattoo, “the words ‘THUG LIFE’ inked in three-inch-high block letters” — the key letter, the I, an image of a lead bullet pointing upward to the head. The highlight reel spins faster and faster, and then, in a flash, he is gone.

A memorial mural for Tupac Shakur by artist Andre Charles on New York’s Houston Street in 1997. (Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Part of the Tupac legend is the eerie certainty of his premature death. On the set of the film “Juice,” a producer, Neal Moritz, “congratulated him for his performance and teased him about spending so much of his money on gold chains and rings.” Tupac simply quoted Robert Frost: “So dawn goes down to day/ Nothing gold can stay.” Moritz, undoubtedly flustered, insisted that Tupac was “going to be a big star in ten years.” (In truth he already was one.) “I’m not going to be alive,” Tupac responded. One could point to half a dozen songs in his catalogue that foreshadow his imminent demise. In any other artist, such an intensely morbid preoccupation could easily stifle our willingness to listen. In Tupac’s work, though, there’s a persistent feeling that he’s never talking about just himself, that he’s the conduit for an immense volume of shearing pain, the cry of a people living under the heel of oppression but also destroying each other in a terrifying, deadly spiral. It is an instantly unforgettable voice: warm and sinewy, fearless but troubled, archangelic. His delivery — breathy, heaving and bluesy, with his famously stretched vowels that accordion their way across the beat — gives his flow an almost overbearing force that sometimes gets squeezed into a syllabic Gatling gun and sometimes gushes like an open hydrant.

Certain artists seem to have, or perhaps borrow for a time, an epic voice, a voice in which a people recognize themselves. Umm Kulthum was an epic voice in the Arab world; Héctor Lavoe was such a voice for Puerto Ricans. Hip-hop has produced a dazzling array of memorable and exquisite voices. But go and listen to “Better Dayz,” or “Starin’ Through My Rear View,” or “Never Had a Friend Like Me,” or “Pain,” or “So Many Tears,” or “Lord Knows,” or “Dear Mama,” and it’s like 40 years of Black American history pours into the ear, and for those who can be touched, it goes to the heart — and hurts. There is no other hip-hop artist of whom I hear it so often said, and by all kinds of people, from all walks of life, that their music helped listeners “get through something.” To read Robinson’s magnificent biography, to follow the jagged spark of Tupac’s life through her pages, is to see how one human being could end up becoming the cause of so much emotion and, at times, a balm for it.

There is a powerful and often recycled notion that the poor, the downtrodden, the oppressed should discover a right way — a righteous path to resist and overcome their condition. From the beginning, the criticism of Tupac (and of hip-hop more generally) was that he shouldn’t be emulated, that his music, his expression, his style and his vulgarity were dangerous, self-defeating, tragically misguided, the wrong way. That critique has always depended on neglecting the question of accountability for the conditions of the society into which he was born. Tupac chose to place his art and his brief life in the name of, and in the service of, the people traveling along the wrong way, the people our society most despises and discards. What do we call someone who offers themselves in that way, who wills their fate down that path? One place to look for an answer is in the pointed irony in one of Tupac’s most celebrated records, “Changes.” That song describes a society that has arrived at an aporia, a state of changelessness and hopelessness, an ugly time when history and the social order can’t and won’t budge, when cycles of destruction self-perpetuate. Tupac makes this diagnosis and calls on us to change it anyway:

We gotta make a change

It’s time for us as a people to start makin’ some changes

Let’s change the way we eat

Let’s change the way we live

And let’s change the way we treat each other

The conviction is unmistakable: It cannot end here. The demand is no less righteous whether we fail in our attempt or whether the messenger will not live to see our works. We know he is speaking truth. It is on us to make the changes that everyone on this planet needs; to bring an end, as Tupac said, to the “war on the streets and the war in the Middle East.”

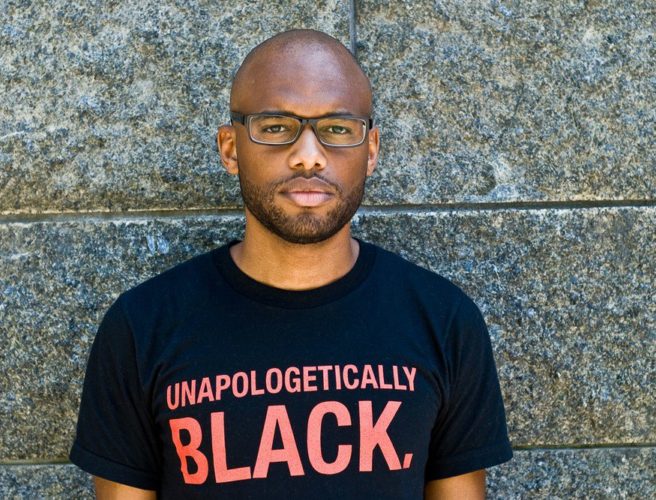

Jesse McCarthy is an assistant professor in the departments of English and of African and African American studies at Harvard University. He is the author of “The Blue Period: Black Writing in the Early Cold War,” the essay collection “Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?” and a novel, “The Fugitivities.”

Tupac Shakur

The Authorized Biography

By Staci Robinson

Crown. 426 pp. $35

The subject of the black family and its relationship to racial progress in America has never been neutral. Historians, social scientists and armchair critics from all quarters have led fractious debates defending or condemning it. These polemics all too often overshadow the very human experience they purport to understand, reducing to caricature full and entangled lives.

In her luminous and remarkably assured first novel, “A Kind of Freedom,” Margaret Wilkerson Sexton cuts through this haze to shine an unflinching but compassionate light on three generations of a black family in New Orleans who try to make the best choices they can in a world defined at every turn by constraint, peril and disappointment — a world in which, as one of her characters puts it, you quickly “learned the hard way that life could drag disgrace out of you.”

For a debut novelist to take up such charged material is daring; to succeed in lending free-standing life to her characters without yielding an inch to sentimentality — or its ugly twin, pathology — announces her as a writer of uncommon nerve and talent.

In “A Kind of Freedom,” Sexton pursues a family’s history in a downward spiral, with three alternating plot lines that echo one another along the way. The novel opens in 1944, with the budding love of Evelyn, a daughter of a well-to-do family (her mother is Creole, her father a black doctor who has raised himself to respectability), and Renard, a young man from a poor Twelfth Ward neighborhood who works menial jobs at a restaurant but aspires to study medicine. Their courtship, though ardent, reveals the strictures of a class- and color-riven society that suffocates ambition and distorts desire.

Forty years later, Evelyn’s daughter Jackie is a struggling single mother in 1980s New Orleans who is in love with her child’s father but afraid he will succumb to his crack addiction. Eventually, we get to know Jackie’s son, T.C., in 2010, a young man at a turning point in his life. Through T.C.’s eyes, Sexton portrays a post-Katrina New Orleans where the smell of mold still lingers and opportunities for fast cash in the streets abound, as do the chances of getting shot or arrested.

Sexton is a native of the Crescent City, and one of the pleasures of this novel is its feel for the particulars of local language, texture and taste: a jar of pickled pig lips, a family crawfish boil, the turn of an old Creole phrase, the sound of Lil Wayne on Q93 FM, as well as the shame of bringing a date to the movies when you had to sit in what was then (in more polite circles) referred to as “the Negro balcony.”

All this can bring to mind Jesmyn Ward’s “Salvage the Bones,” but where Ward is Faulknerian in her rhetorical sweep, Sexton maintains a cool, detached naturalism more reminiscent of Tayari Jones in “Leaving Atlanta.” Whether writing of black girlhood, the quotidian fears and hopes of mothering, or the lure of street life, she places her characters in the path of momentous choices while making it clear they have little to hope for. At the end of the day, it is mainly women like Jackie, “teetering between her narrow options,” who are left to pick up the pieces and wonder at their ability to cope. “What happened to the face of a broken woman?” Evelyn asks herself as she watches over her sleeping sister. “Did it turn to convey the loss or did it conspire with her heart to hide it?”

“A Kind of Freedom” attends to the marks left on a family where its links have been bruised and sometimes broken, but dwells on the endurance and not the damage. The force of this naturalistic vision is disquieting; it is also moving. One could say that it has the disenchanting optimism of the blues. Though her style differs sharply from Zora Neale Hurston’s sassy lyricism, Sexton looks upon her characters much as Janie views her life in “Their Eyes Were Watching God” — “like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone.”

Percival Everett. So Much Blue. Graywolf Press, 2017.

One of the great, unsung heroes of the 1970s is a black cowboy by the name of The Loop Garoo Kid, the hero of Ishmael Reed’s 1969 novel, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down. In Reed’s tall tale, a brilliant spaghetti-noir—A Fistful of Dollars meets Killer of Sheep—Loop Garoo is a wandering cowpoke who also happens to be a fiercely independent experimental novelist. Early in the novel, The Kid gets ambushed on the edge of the desert by “Bo Shmo and the neo-social realist gang.”

“The trouble with you Loop is that you’re too abstract,” their leader declares, “far out esoteric bullshit is where you’re at. Why in those suffering books that I write about my old neighborhood and how hard it was every gumdrop machine is in place while your work is a blur and a doodle.” Loop keeps his cool and answers his truth: “No one says a novel has to be one thing. It can be anything it wants to be, a vaudeville show, the six o’clock news, the mumblings of wild men saddled by demons.” The neo-social realists have no answer to this, and “being not very original,” decide to discipline Loop by smearing jelly on his face and burying him up to his neck in the sand.

Loop Garoo’s fix is that of all writers struggling to define themselves against a tide of assumptions about who they are and how they ought to exercise their craft. But he’s also very specifically an avatar for the figure of the black writer in America, struggling to outrun the ambushes of racist strictures—the demand that one focus relentlessly on “how hard it was” in the “old neighborhood” or face accusations of betrayal and questions of authenticity, while simultaneously be ignored if one deviates from the expected script. In short, it’s the old canard that the black writer faces a zero-sum choice between political responsibility and alienated indulgence. I suppose it is for this reason, along with the Western theme, that the perilous path of the Kid reminds me of no other contemporary writer more than Percival Everett, a writer whose thirty-year career has produced a dazzling and prolific array of experimental novels, short stories, and poetry that have won him something of a near-legendary reputation himself, an outsider roaming the American West where he has long made his home.

n France, there is a distinct, almost literary pleasure in watching the unlikely rise of a handsome, ambitious young man from the provinces and charting his skillful navigation of the treacherous corridors of power, vanity, and ambition. But as Balzac and Stendhal knew well, the motif is also useful as a means of exposing the surprisingly shoddy scaffolding of government—the remarkable extent to which the majesty of state power, upon closer inspection, reveals itself to be a delicate facade masking ugly, unprincipled, and chaotic struggles for domination.

The triumph of Emmanuel Macron in the 2017 French presidential election is undoubtedly novelistic in this sense. At the tender age of 39, Macron is the youngest man ever to become the head of the French republic. Born in Amiens, historically the provincial capital of the northern region of Picardie, he grew up in a solidly bourgeois household. Both of his parents are doctors, and he attended Jesuit schools in the region before going to Paris to enter the Lycée Henri IV, one of the country’s most prestigious high schools. A precocious and gifted student, he evinced a passion and a flair for the dramatic arts—skills that have transferred well to his political role and influenced his personal life. In 2007, he married his theater teacher, Brigitte Trogneux, 24 years his elder and the daughter of a prominent family of chocolatiers known for their macaroons and their right-leaning politics. With a stellar résumé, he passed through the nation’s business and administrative grandes écoles, institutions that have become rites of passage for those seeking to enter the upper branches of state power. His trajectory, in short, has been that of an impeccable golden boy who is more acquainted with success than failure, who has enjoyed the fruits of being born into comfortable circumstances, and who possesses exquisite social-climbing skills and an unerring sense of good timing.

On the evening of his election victory, Macron strode out alone in a long, dark coat, under dramatic lighting, and into the main square in front of the Louvre. He faced I.M. Pei’s glass pyramid as loudspeakers played the official hymn of the European Union, Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” It was a pointed musical choice, reflecting the view, at home and abroad, that Macron’s victory was a make-or-break moment for the European project, which has recently been imperiled by Brexit, the turmoil in Greece, and the contempt of the Trump administration. More subtly, local political observers also interpreted it as a nod to François Mitterrand and the 1981 election that brought the Socialist Party to power for the first time since World War II: The Louvre’s glass pyramid was one of Mitterrand’s iconic grand projects, and he also chose the “Ode to Joy” as the musical accompaniment for his victory lap.

Don’t expect Macron to lead a return to socialism, however. In fact, his rise to power, and the hope that it has understandably brought to a portion of the French people, actually embodies, and even magnifies, the extent to which the political foundations of the French republic are rotten. Macron’s story symbolizes, for many, not the potential to rise from lowly beginnings to the highest office in the land, but rather the entrenchment of social inequality that protects a culturally liberal, bourgeois class with anti-labor economic priorities. Macron represents a class of French citizens that has flourished under left- and right-wing governments alike, has refused to make any concessions to those who have been left out, and has become increasingly insulated from popular demands to end tax evasion by the wealthy, nepotism in government, and a eurozone monetary policy dictated from Berlin.

Joshua Bennett is one of the most impressive emerging voices in poetry today. His debut collection, The Sobbing School, written in 2014 against the backdrop of a national crisis over state violence and black lives, won the 2015 National Poetry Series Award and is published this fall by Penguin—you can read three of his poems in the current issue of Dissent. Although he is making his debut in print, Bennett is already well known as an artist of the spoken word, whose performances have gained him a huge following on college campuses. He is also quietly building a reputation as one of the brightest intellectual and political thinkers of a new generation, and is currently a member of Harvard’s Society of Fellows.

I first met Joshua at Princeton in the fall of 2011. Over five years of graduate study together, he has been a vital friend and a source of constant intellectual inspiration. He is the kind of person who gets you excited about thinking and reading again. In the pages of Dissent last year I suggested that his voice is part of a literary movement in which poetry and politics are converging in new and unexpected ways, exemplified, for instance, by the success of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. This September we met at Dissent’s office in downtown New York City to talk about the origins of his book, affect in poetry and politics, and what solidarities and imaginaries might point us towards a more hopeful future.